1984-1998

1984-1986

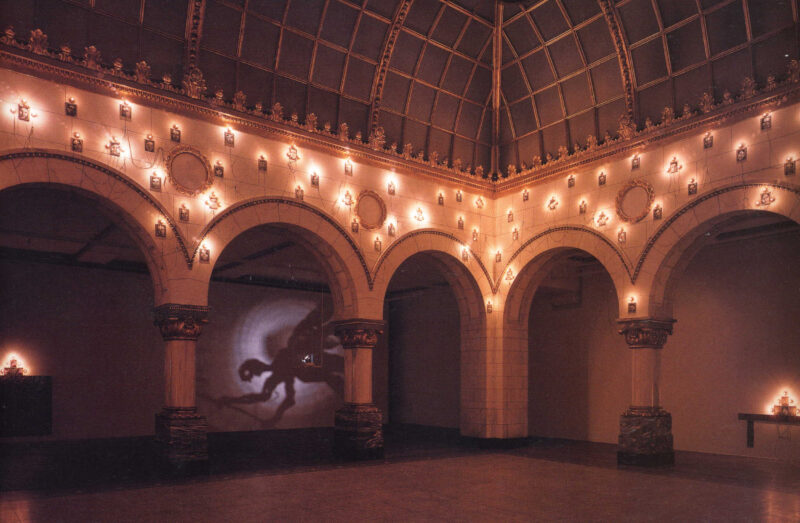

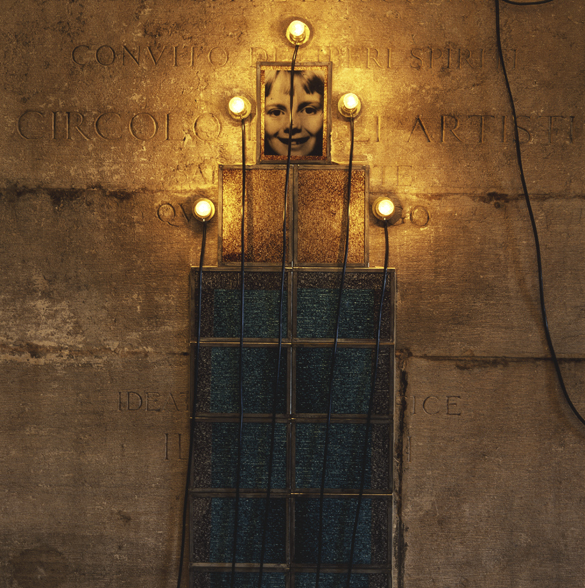

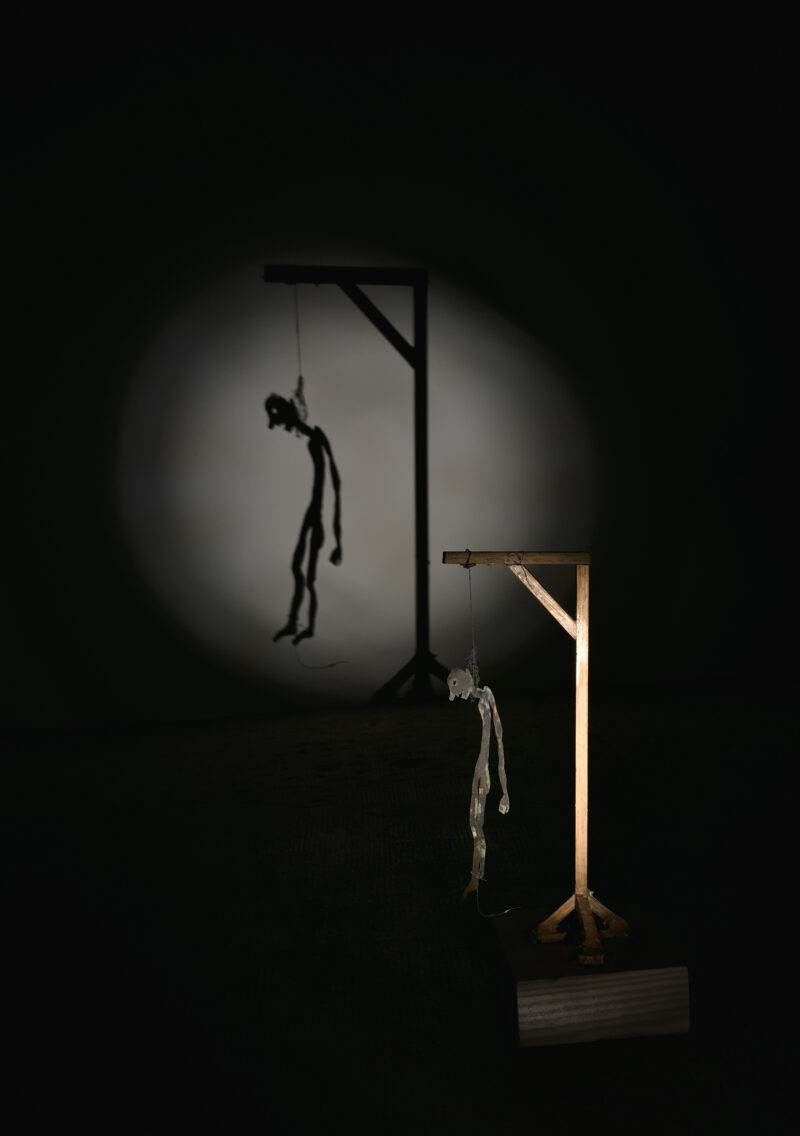

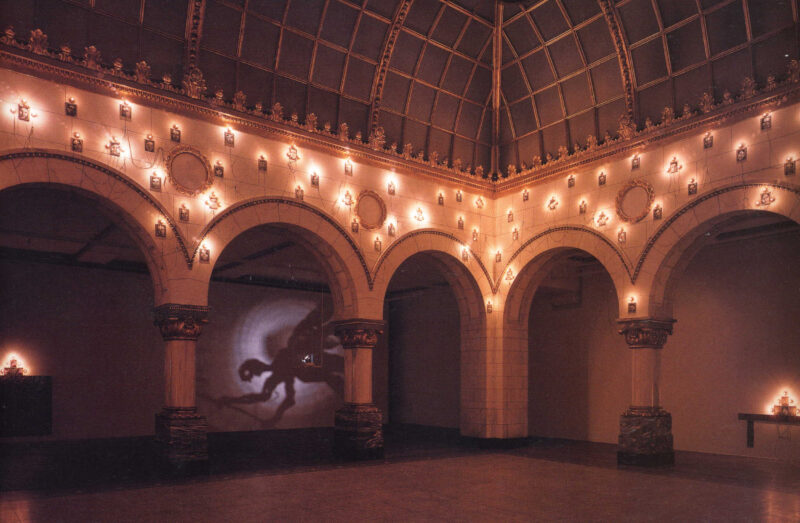

The years 1984 to 1986 were a dark and anxious period marked by the loss of his father. Boltanski focused on assembling and building works as he had in his early career and began to make more use of space. He created figures with items found on the ground around his new studio in Malakoff (just south of Paris), such as twigs, pieces of wire and tree bark. This work gave rise to his Théâtres d’ombres (Shadow Theatres), the first of which were shown at the Galerie’t Venster in Rotterdam in 1984 and at the Paris Biennale at La Villette in 1985. Angels, skeletons, hanged figures, the Grim Reaper and other apocalyptic motifs took over the walls in danses macabres.

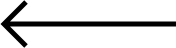

When he was invited by the Le Consortium museum in Dijon to execute an installation in situ, Boltanski drew on another piece he had produced in Dijon in 1973 at the Les Lentillères secondary school, where he covered the walls of a corridor with photographs of the students, in the manner of a columbarium. With the idea that after ten years the children would now be adults, he made Les Enfants de Dijon (The Children of Dijon), attaching light bulbs and cables to their enlarged portraits. He then created his first Monuments in 1986, adding monochromatic prints of blue, red and gold metallic Christmas paper in pyramid and altar-shaped compositions. The same year, for the Festival d’Automne in Paris, he presented a memorable exhibition at the chapel of the La Salpêtrière Hospital, where his father had died two years previously. Leçons de ténèbres (Lessons of Darkness), his first site-specific installation, marked a turning point in the artist’s career. He began to change the way his works occupied space and became increasingly interested in non-museum locations, where visitors could experience a situation in which they would wander around dimly lit works in semi-darkness. Unearthing images he had used in his early books and in his Dijon installation, the artist turned the practice of recycling into an act of salvage. He favoured humble and very ordinary materials such as paper, iron, light bulbs, highlighting the precariousness of life. Weak light and wires, representing the fragility of life, became fundamental elements in Boltanski’s artistic vocabulary. From 1986, his highly symbolic works carried their own lighting.

With this ensemble of works he was introduced to a wider public and gained recognition in America, thanks to the ‘Lessons of Darkness’ exhibition curated by Lynn Gumpert and Mary Jane Jacob, which took place in several major American museums, including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the New Museum in New York.

1987-1990

The commemorative aspect that now characterised Boltanski’s work brought new historical interpretations. For the series ‘Le Lycée Chases’ (The Lycée Chases) and ‘La Fête de Pourim’ (Purim), he used two pre-war images showing two groups of smiling people. The first was a final-year class photograph from a private Jewish school in Vienna, the second a group photograph taken at a Yiddish school in Paris in 1939. Between 1987 and 1990, he executed several works using these photographs, reframing and enlarging them until they became blurred, or combining them with biscuit tins and clip lamps: the Reliquaires (Reliquaries) and the Autels (Altars). The blowing up of the faces stripped individuals of their identity, celebrating instead a mass united by a common destiny. The presence of the biscuit tin referenced our humble relics.

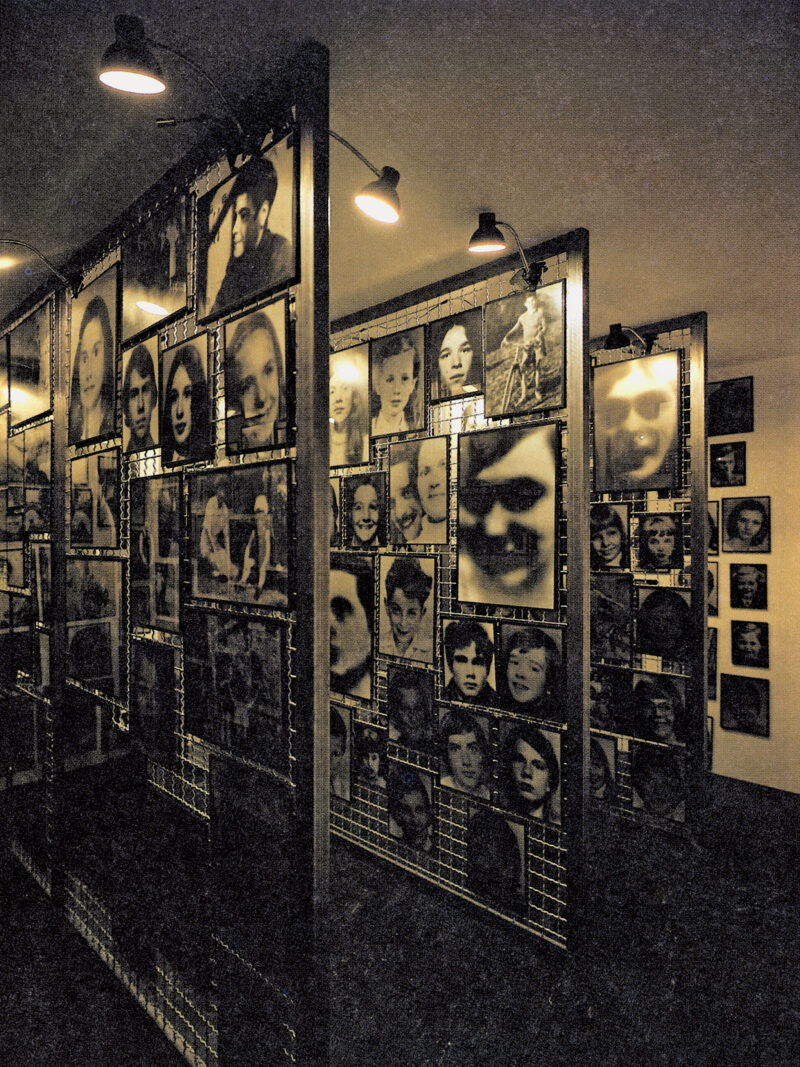

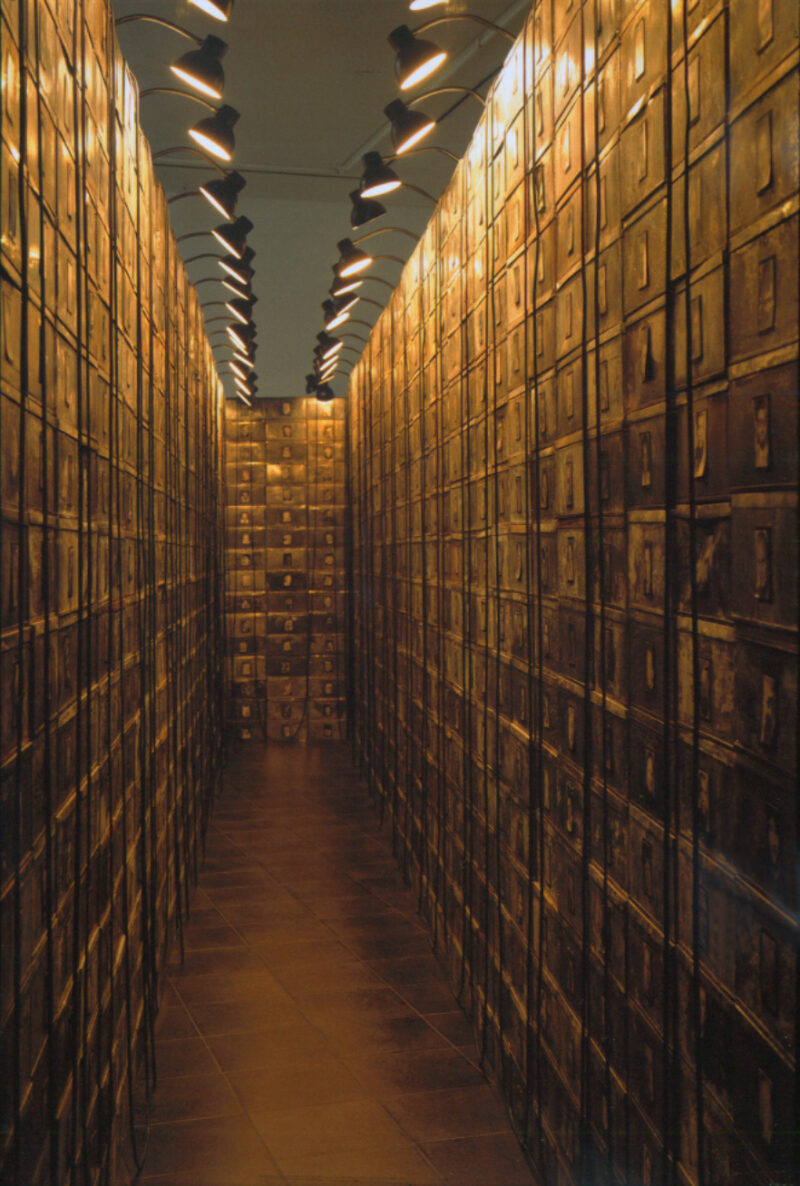

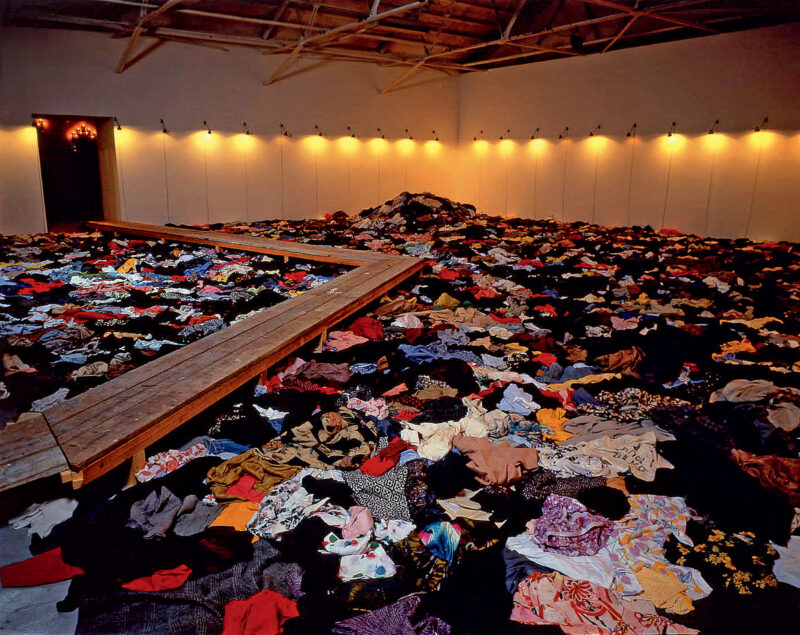

In the same period the artist created large-scale settings such as the Archives, presented at ‘documenta 8’ in 1987, and the Réserves, the first of which (Canada) was mounted in 1988 at the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation in Toronto. Hundreds of blown-up photographs of faces hang side by side on a grille; thousands of items of clothing cover the walls, shelves and floor; boxes are piled up precariously. With La Réserve des Suisses morts (The Reserve of Dead Swiss), by choosing a people ‘without history’, he highlights the banality of death. After 1990, he displayed photographic portraits taken from Swiss obituary columns with cardboard or rusty iron boxes to fill oppressive corridors (Carnegie International, Pittsburg), build walls (Marian Goodman, New York, 1990), or create dizzyingly tall piles (Galerie Hussenot, Paris, 1991). And even if every carefully labelled box carried an identification photo and contained the corresponding obituary notices, they were just thousands of abandoned boxes, thousands of photos of individuals that nobody recognised any more.

Yet while commemorating these dead, Boltanski underscores their permanent loss by undermining the notion of memorial permanence. His own life was also commemorated in a similarly sterile construction. The artist built his own memorial, Les archives de C.B. 1965-1988 (The Archives of C.B. 1965–1988), in the form of 646 biscuits tins containing 1,200 photographs and 800 documents.

1991-1995

Invited with other artists to react to the fall of the Berlin wall, Boltanski executed La Maison manquante (The Missing House), based on research carried out by art school students on the residents of a building that had been destroyed. Each resident’s name and date of death appear on plaques fixed to the walls of the neighbouring houses that still stand, at the level of their former apartment. These people living amongst each other are both victims and killers, as in the anonymous crowds of the imposing 1994 installation Menschlich (Human) (which won him the Aachen prize in 1994), where thousands of portraits lining the walls from top to bottom celebrate a huge segment of humanity. In their profusion, these effigies lose their identity even when the artist enumerates them individually. Yet Boltanski even made lists of names: in 1991, he listed the participants at the Carnegie International, in 1995 he inscribed the names of the artists participating in the Venice Biennale on the outside walls of the Italian pavilion, and in 1996 he named the workers in a Halifax factory (The Work People of Halifax 1877-1982).

Lists abound in the artist’s books that Boltanski continued to create – lengthy, fastidious lists without commentary or photographs, such as the telephone directory listing of Malmö residents in 1994. His use of clothing is even more revealing. In this period, he began to compose works with a coat or several coats, sometimes left on a chair, or laid on the ground like dead bodies, or nailed onto the wall with the sleeves spread out in a clear religious reference.

In the early 1990s, he started his collaboration with the Marian Goodman Gallery, which remains his gallery to this day. In 1991, he exhibited works at the Musée de Grenoble in ‘Reconstitution’, an exhibition that travelled to the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Whitechapel Gallery in London and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. He presented several exhibitions in major European museums, including the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, the Städtisches Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach, the Reina Sofia in Madrid, the Belvedere in Prague, the Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea in Santiago de Compostela, the Kunsthalle in Vienna. He exhibited work in Japan for the first time at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Nagoya, in 1990, and maintained close relations with the country after that date. After a stint with the Bordeaux education authority, he started teaching at the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, practising such as a Socratic method. His friendship with Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Absalon were of great importance; he shared with the former a sense of the poetry of the ordinary and appreciated the latter’s brilliance.

1995-1998

An obsession with death marks the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Boltanski lost several of his friends to AIDS. Between 1996 and 1998, he produced five symbolic pieces: Les Tombeaux (Tombs), showing the impartial cruelty of death; Les Portants (Hanging Rails), referencing sickness and hospitals; Les Concessions (Concessions), in which he conceals the horror of multiple deaths behind black cloths; Les Véroniques (Veronicas), ghostlike, neon-lit photographs covered with a cloth; Les Lits (Beds), evoking morgue stretchers. In all of them a veil shields the obscenity of death.

Boltanski worked on multiple projects in which he explored new ways to present his work. He collaborated with numerous curators, including Hans Ulrich Obrist with whom he organised the famous ‘Take Me (I’m Yours)’ show in 1995 at the Serpentine Gallery in London, where visitors could take away objects exhibited by the artists. The project was repeated many times throughout the world. During these years he closely followed the work of Pina Bausch: in the relationship between the dancers’ bodies, he recognised his own attempts to represent the human being, and the same attraction to unusual practice within the discipline.

Boltanski was fascinated by staging, and with Jean Kalman, whom he met in 1984, he directed performances in which the audience would be wandering around. After the dramatized version of Schubert’s Winter Journey, directed by Hans Peter Cloos at the Opéra-Comique in 1993–94, the two worked together again in Derniers jours (Last Days) after Sleeping Beauties for the Festival d’Automne in 1997.