1944-1984

1944-1969

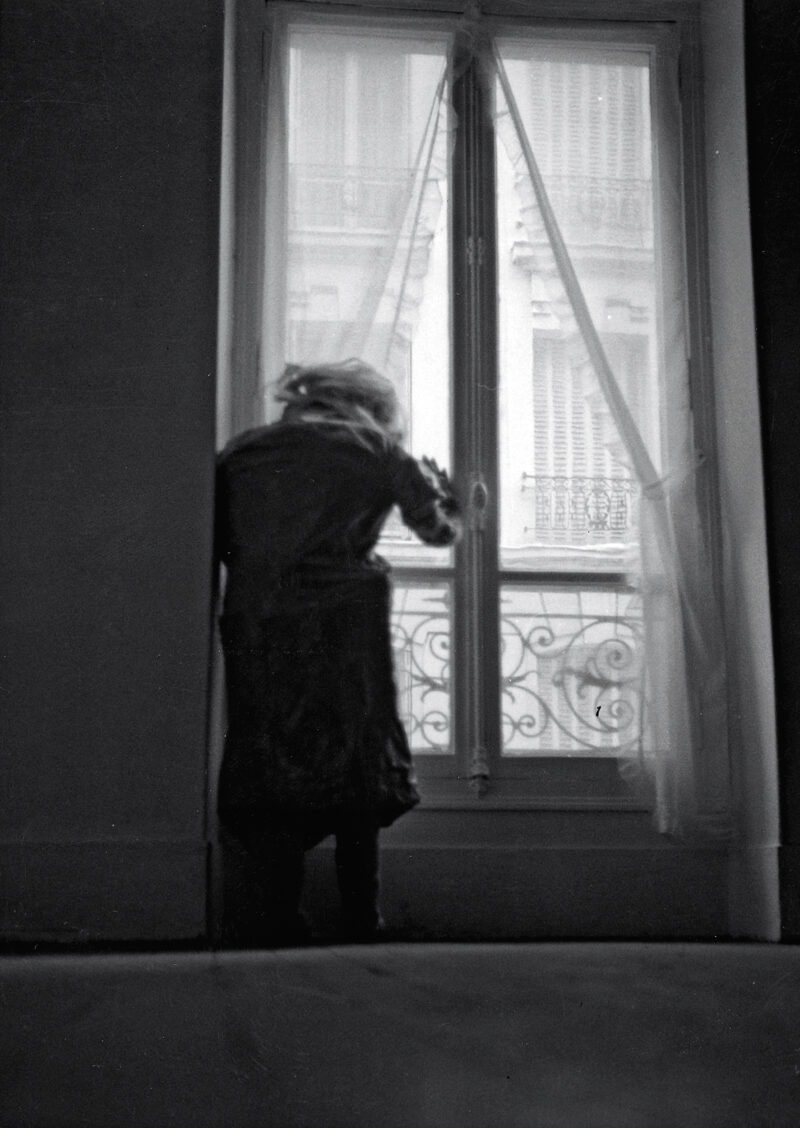

Christian Boltanski was born in Paris on 6 September 1944. His father was a physician of Russian Jewish origin, converted to Catholicism, and his mother a writer of Corsican origin and a Catholic, who suffered from the after-effects of polio. She wrote several books under the pen name of Annie Lauran. Much has been written about his unconventional childhood, his father hiding under the floorboards of the house, the family’s fear that forced them always to move, sleep and live together, his bohemian relations, his curtailed schooling.

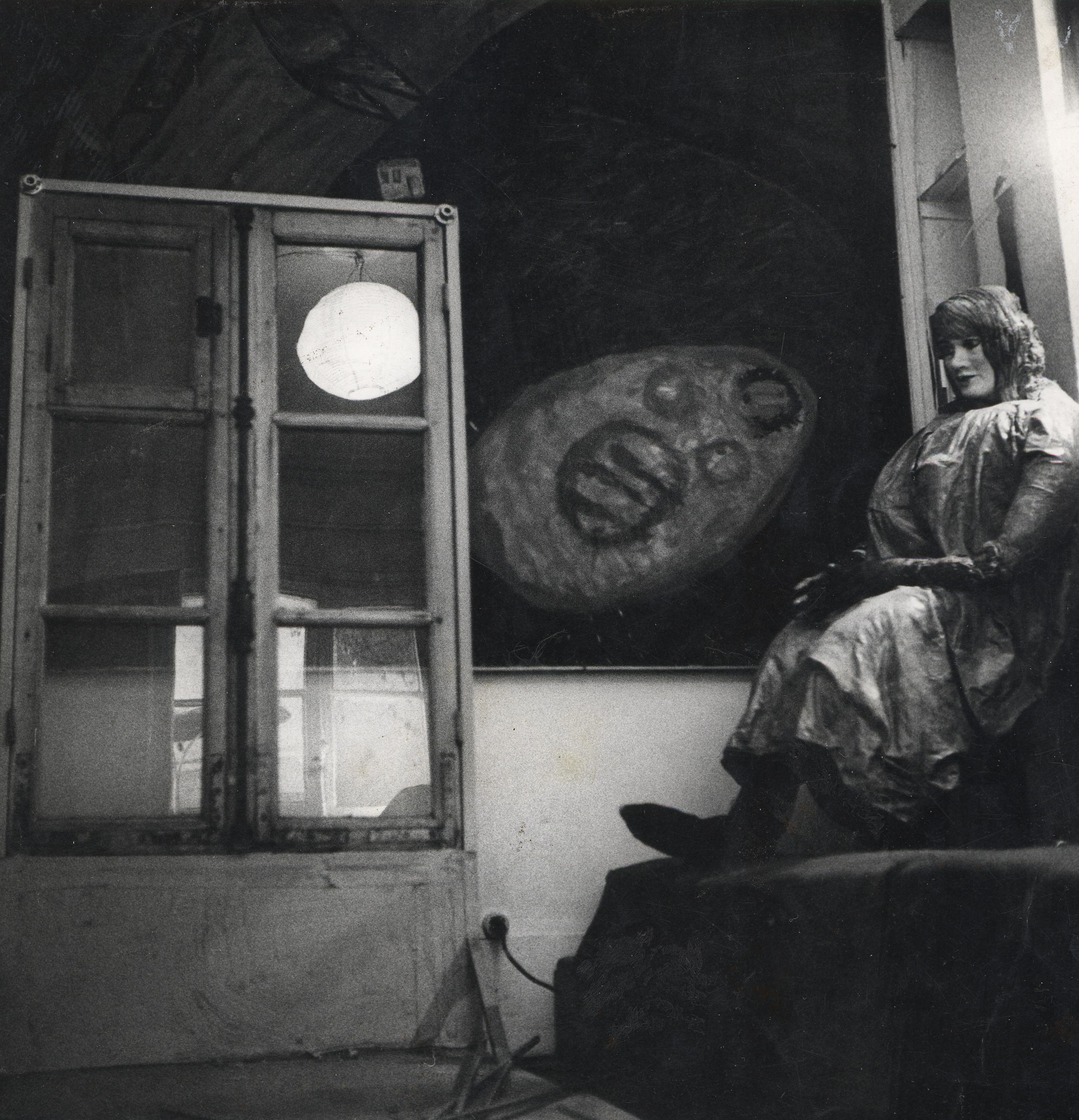

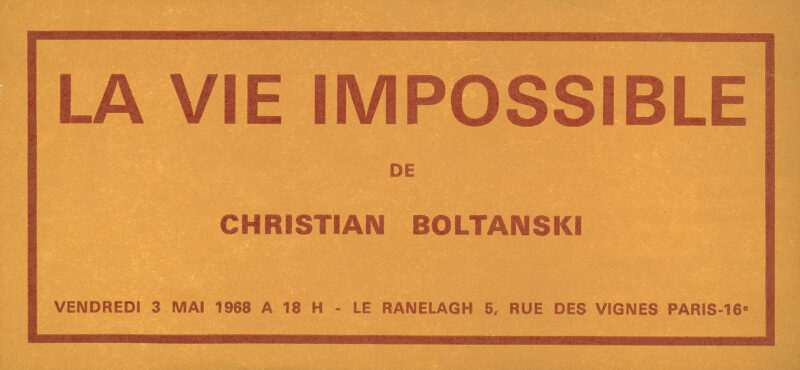

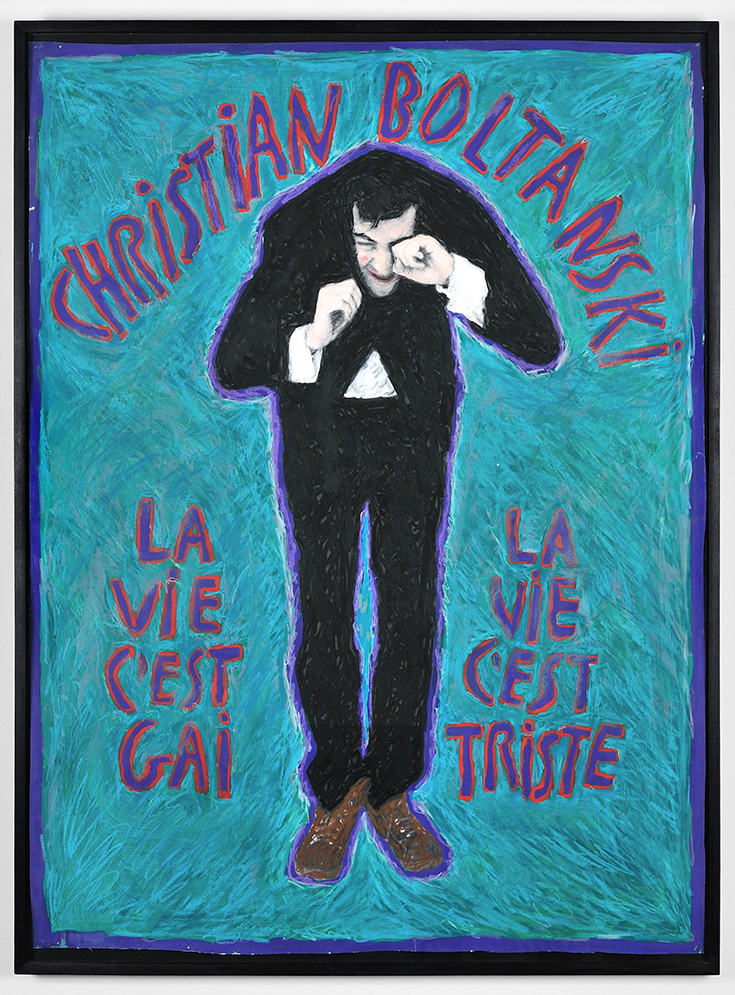

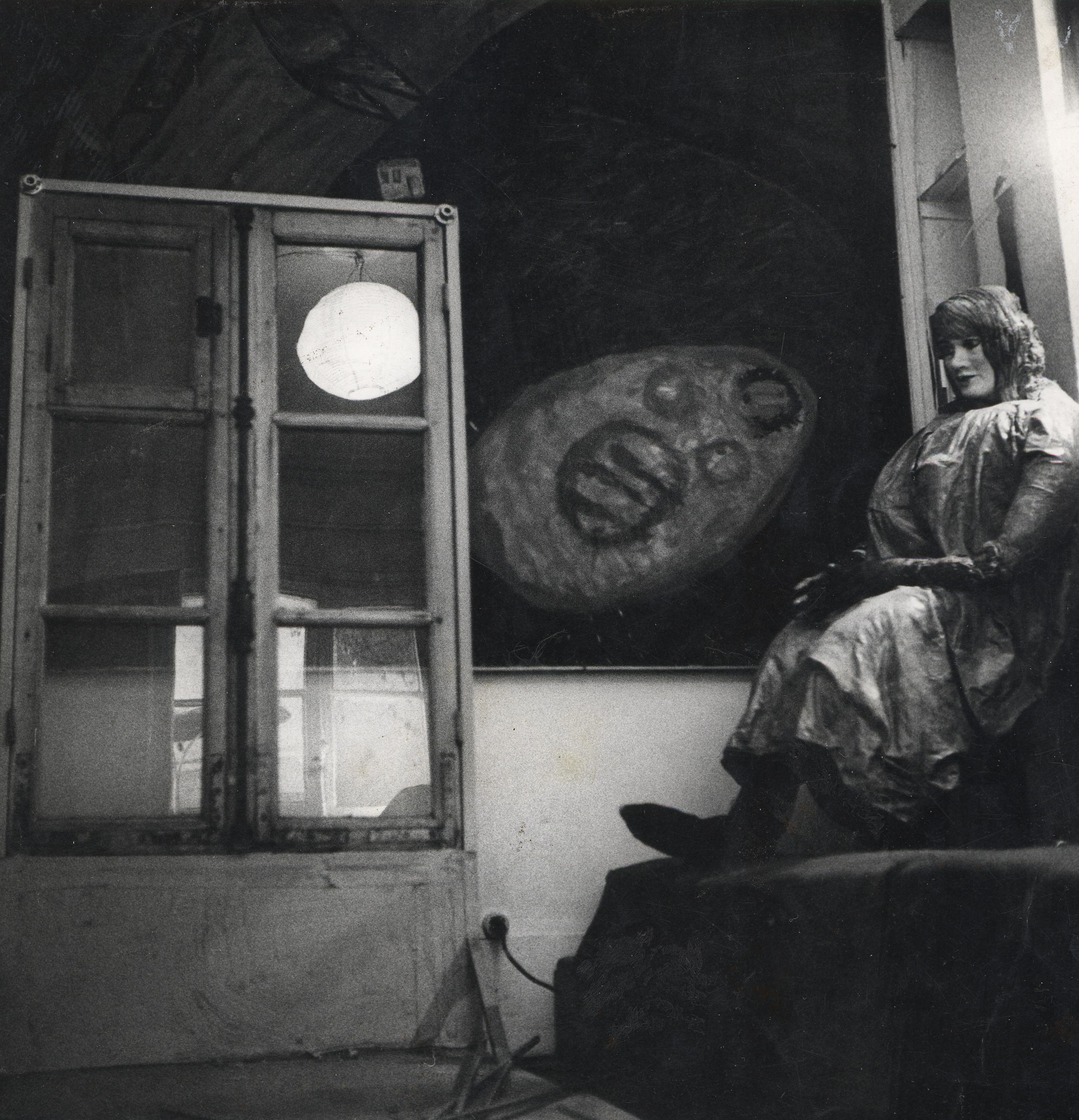

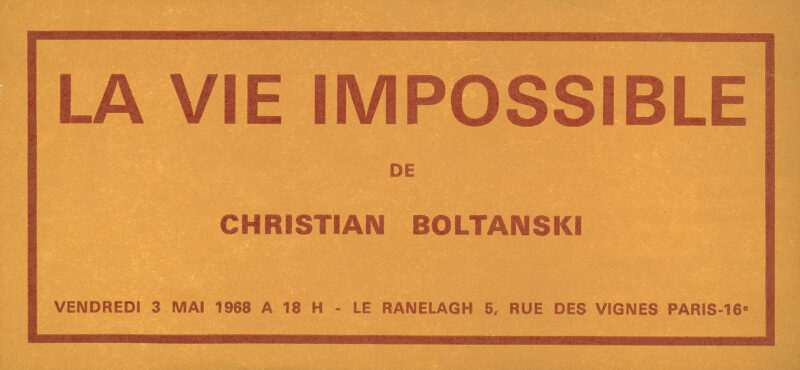

He lived in considerable isolation until the age of twenty-four, and during this period painted hundreds of oils and gouaches on board and made large dolls that he used in very short expressionist films. The title of his first film, La Vie impossible de Christian Boltanski (The Impossible Life of Christian Boltanski), made in 1968, was borrowed for his first solo exhibition, at Theatre du Ranelagh in Paris in May of the same year.

For a few months he ran a tiny gallery named Tournesol on Rue de Verneuil, where he got to know several young artists; among these was Jean Le Gac, with whom he became friend and took part in group exhibitions, including the 6th Biennale de Paris. On this occasion, with Jean Le Gac and Gina Pane, he created Concession à perpétuité.

1969-1972

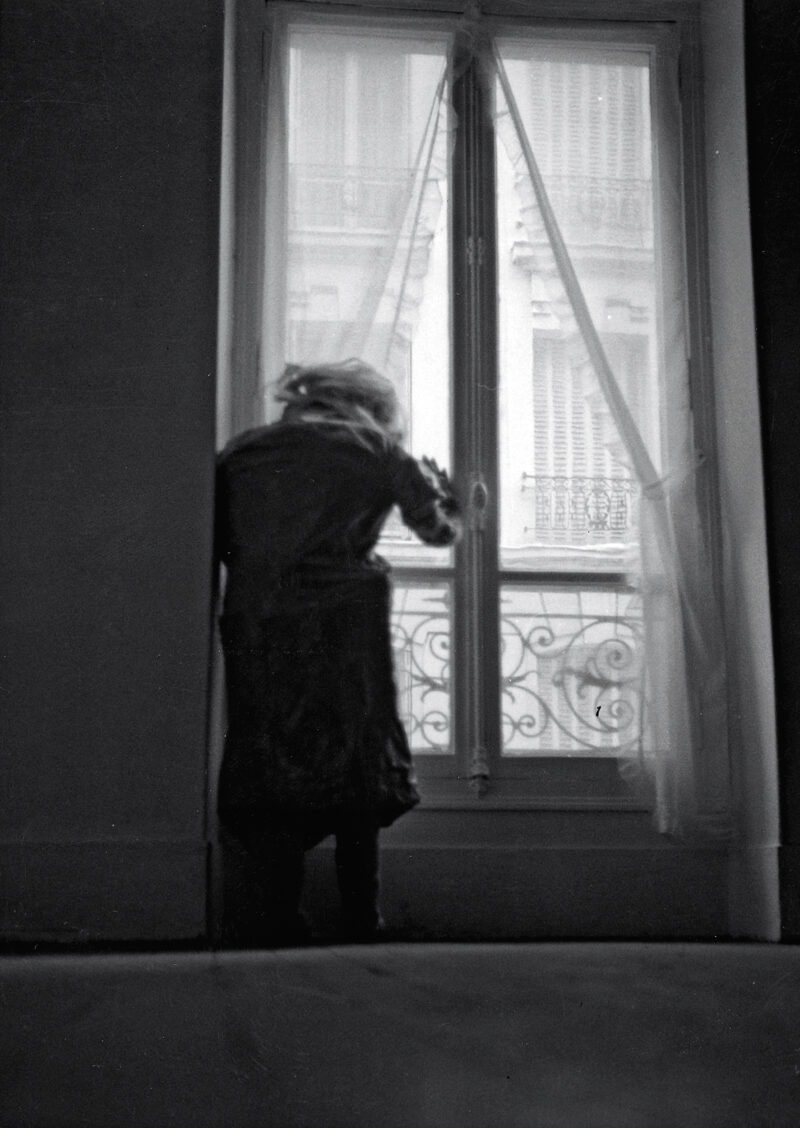

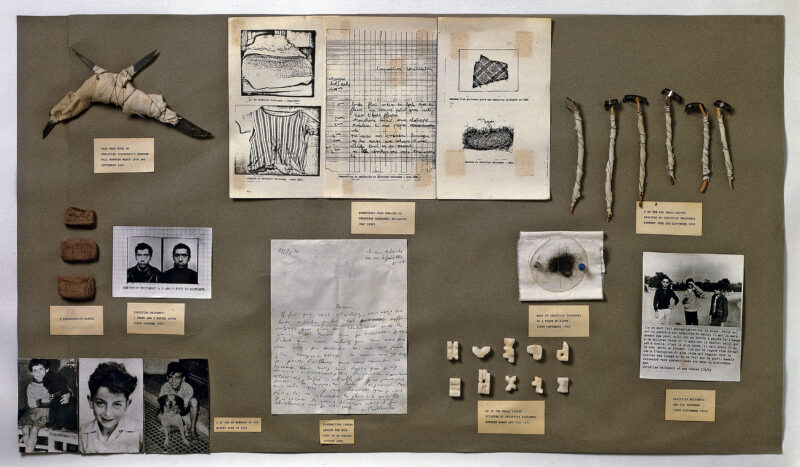

In 1969 he began work on various reconstructions of his childhood, in opposition to the inexorable loss brought about by death. His approach centred on a quest for disparate fragments of his past, through regeneration, using photographs of events, often insignificant but that had been preserved in his memory, or through the reproduction in clay of objects that had belonged to him.

At the time he frequented the Givaudan gallery, where he had access to an offset machine. Here he produced his first reconstitution: Recherche et présentation de tout ce qui reste de mon enfance 1944-1950 (Research and Presentation of All That Remains of My Childhood, 1944–1950). The work was sent by post in May 1969 and is comprised of nine photocopied pages held together by a plastic slide binder, including a founding text and photographs, including a class photo showing himself as a child. This was the first in a long series of artist’s books, and it laid the foundation of his oeuvre.

During this period Boltanski was part of a group of artists interested in a narrative form and gravitating around Jean Clair and the journal L’Art vivant. At the Salon de Mai in 1970 he met Annette Messager. In late 1969, Boltanski executed several works with Jean Le Gac, notably installations in an apartment at 41 Rue Dumoncel, Paris. Together with Jean Le Gac and Paul-Armand Gette, he performed nine walks, announced on cards that the public received once the walk had been completed. He was also involved in collective works produced in non-institutional locations with the artists mentioned above as well as André Cadere and Bernard Borgeaud.

This period, marked by enigmatic postings containing melancholic messages, remnants from his daily life (strands of hair, a white card with the work ‘maladie’ [illness] typed on it, a letter asking for help), was also one of repetitive, obsessive artistic acts. These cathartic works, such as sugar lumps carved into shapes and thousands of moulded clay balls, gave rise to a series of objects exhibited at the Musée Galliera in 1969. Besides these were small knives made with razor blades and traps full of needles that were shown in an exhibition with Sarkis at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, carefully arranged in showcases like archaeological relics. This is where he met Ileana Sonnabend, with whom he began a long-running collaboration. It was at her gallery that he exhibited for the first time, in simple tin boxes covered with wire mesh, objects roughly modelled in Plastiline to resemble his toys, tools and clothes.

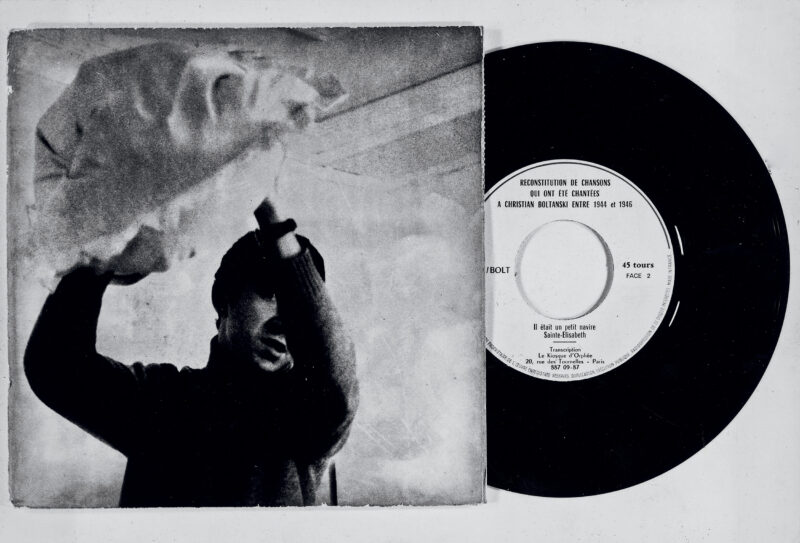

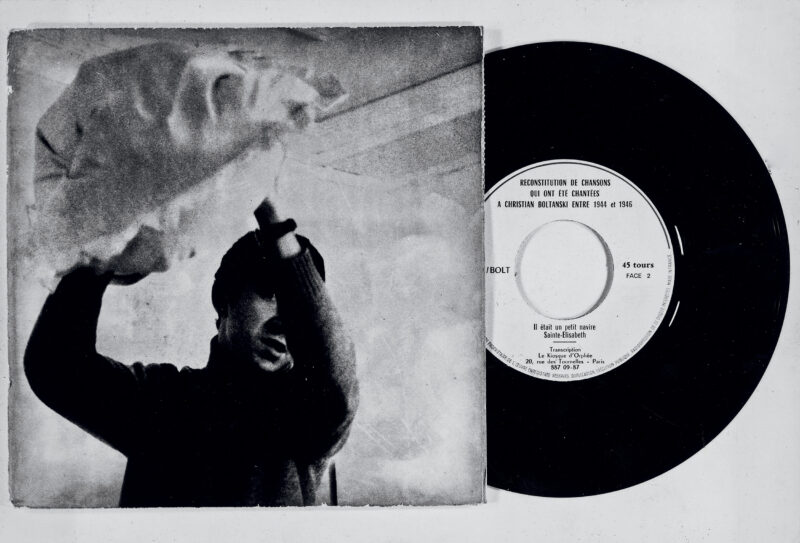

Boltanski designed several small books illustrated with traces of his life, including Essais de reconstitution d’objets ayant appartenu à Christian Boltanski entre 1948 et 1954 (Attempted Reconstitutions of Objects Belonging to Christian Boltanski Between 1948 and 1954), Reconstitution des gestes effectués par C.B. entre 1948 et 1954 (Reconstitution of Acts by C.B. Between 1948 and 1954) and 10 Portraits photographiques (10 Photographic Portraits), which show the banality of each individual’s life while revealing a collective history.

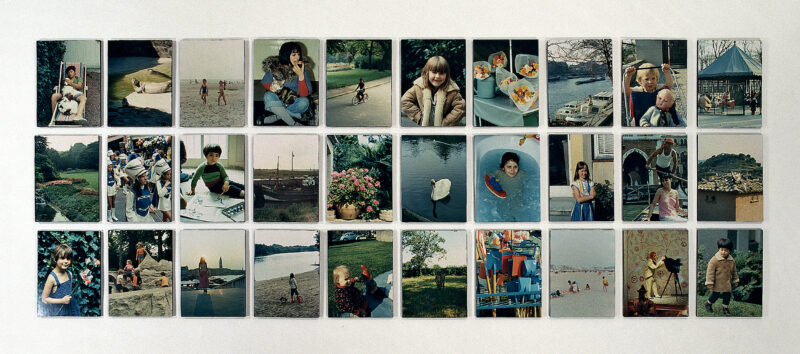

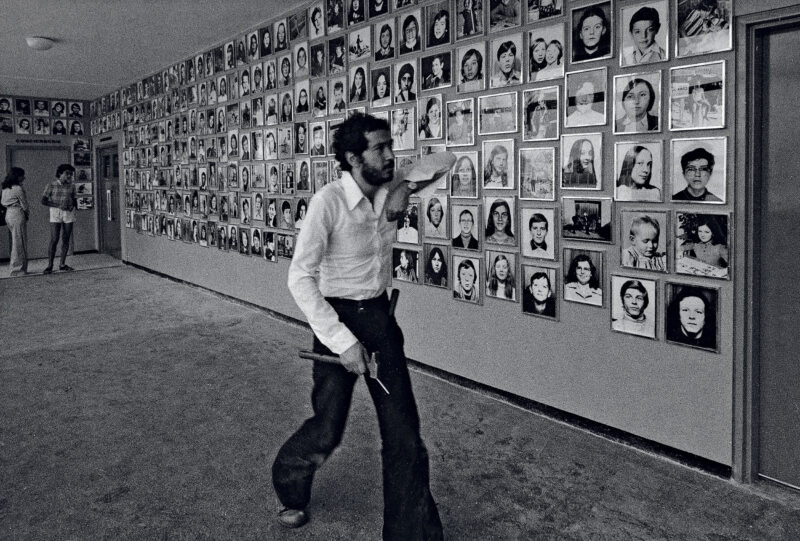

This investigation into his own identity turned into an ontological quest, most successfully represented in L’Album de la famille D. (Album of the D. Family): a collection of family photographs that act as universal codes in their ability to conjure up shared memories. He transposed to it the sociological context he shared with his brother Luc, a sociologist and collaborator of Pierre Bourdieu, notably in Un Art Moyen, published in 1965 (English edition: Photography: A Middle-brow Art, 1990).

This work was first exhibited at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris in 1971, then at ‘documenta 5’ in Kassel in 1972, where the young Boltanski was invited by Harald Szeemann to exhibit in the ‘Individual Mythologies’ section. There he met art critics and discovered the work of artists who would make a lasting impression on him, including Joseph Beuys, Paul Thek, Edward Kienholz and James Lee Byars. The same year, he exhibited work at the 36th Venice Biennale, and at ‘72 – douze ans d’art contemporain en France’ (72: Twelve Years of Contemporary Art in France) at the Grand Palais in Paris, where he showed his Vitrines de reference (Reference Showcases) for the first time.

1973-1984

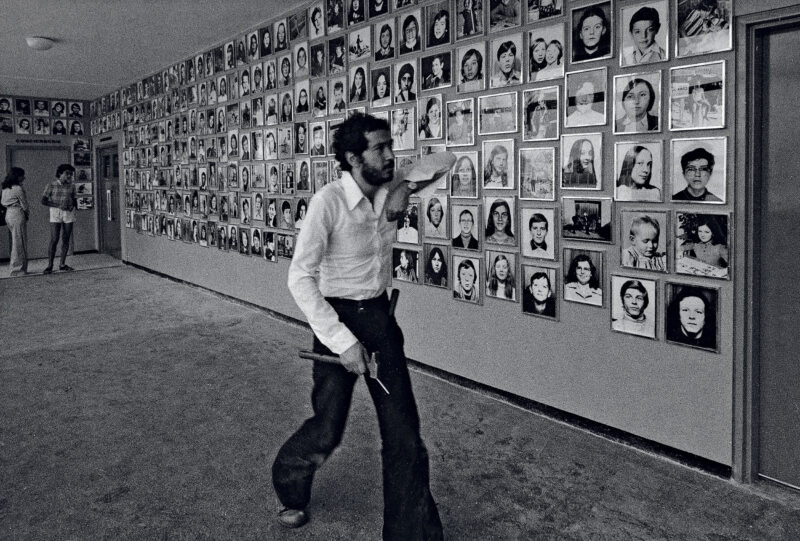

Obsessed by all that passes and is forgotten, Boltanski undertook to make an inventory of what can be preserved, often inconsequential items such as objects from long-lost cultures in the ethnographic collections of the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The inventories, which were always the form taken by most of his work, became installations of objects belonging to strangers. On 3 January 1973, Christian Boltanski sent a handwritten letter to sixty-two museum curators (at art, history and ethnographic museums etc.), proposing an exhibition of objects that had surrounded a person during their life. Some of them accepted his proposal, enabling him to exhibit and label a whole collection of quite ordinary relics, highlighting our individual insignificance and also providing a reflection on museum practice. The first Inventaire (Inventory) was shown in 1973 as part of a group exhibition at the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Baden-Baden.

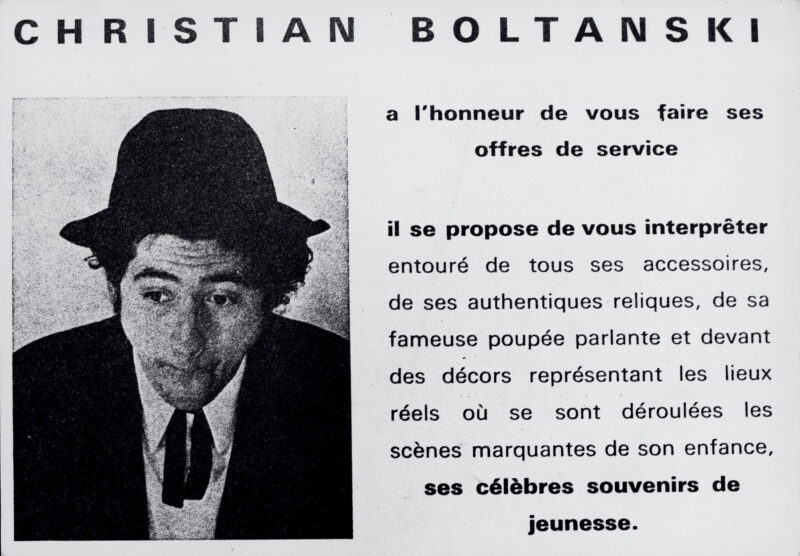

Often described as ‘Proustian’ in the press at the time, Boltanski tried to escape this description by parodying his own biographical collections through a clown to whom he gave his own name. Inspired by the famous German comedian Karl Valentin, who he discovered thanks to Günter Metken, he imagined this clown’s life by creating his accessories and revisiting his memories, for which he played all the roles, staging himself in rudimentary settings. The Westfälischer Kunstverein in Münster hosted the first exhibition of this series of works called Saynètes Comiques (Comic Sketches) in autumn 1974.

From 1975, Boltanski began working on taste and cultural stereotypes, probing photographic codes, and in his Images modèles (Model Images) caricatured happiness by enlarging coveted objects and exploring a child’s sense of wonderment. Artistic trends at the time and the prospect of large-scale museum exhibitions encouraged him to enlarge the format of his photographs. Between 1977 and 1984 he produced his Compositions photographiques (Photographic Compositions), variations on still lifes, in which he tried to fulfil his pictorial aspirations. These were followed by the Compositions grotesques, japonaises, architecturales, théâtrales (Grotesque, Japanese, Architectural, Theatrical Compositions), which were shown to a large number of visitors by the ARC in 1981 and at his first retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1984. On this occasion he exhibited Composition occidentale (Western Composition), a Christmas-tree-shaped piece in which he used for the first time small lights and hanging wires, suggesting candles and garlands.