1998-2021

1998-2003

A partir de 1998, Boltanski commence à concevoir ses expositions comme un parcours symbolique à travers des œuvres qui fonctionnent telles les étapes d’un voyage ou les stations d’une procession. Tel est le propos de l’artiste lors de son exposition « Dernières années » au Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris en 1998. Le public, après avoir traversé les salles avec Menschlich, Les Registres du Grand Hornu, les Lits, descend au sous-sol dans La Réserve des Enfants (œuvre permanente réalisée en 1989) et arrive à la dernière étape, Perdus, où il est entouré des 5000 objets trouvés que personne n’a jamais réclamés. Cette démarche est, comme il le dit lui-même, inspirée par son travail « théâtral ».

Grâce à ces incursions sur la scène théâtrale, Boltanski commence à maitriser la lumière, le son, les déplacements du spectateur. En 1999 avec Jean Kalman, il met en scène Der Ring dans la banlieue de Berlin. Il est accompagné par Ilya Kabakov qui ponctue le parcours avec des œuvres peintes. A l’intérieur de l’ancien sanatorium en ruine de Beelitz, le public erre se laissant diriger par des événements impromptus. Lors de cette dernière mise en scène, l’artiste met au point des principes qui deviendront récurrents : la déambulation du public dans un espace vaste, sombre et de préférence froid où il est sollicité par des évènements plastiques, musicaux et théâtraux. L’éphémère qui domine le monde du spectacle l’attire. Il est séduit par la fugacité d’une mise en scène qui ne pouvant pas se répéter, ne peut, éventuellement qu’être racontée. Sa collaboration avec Jean Kalman donne lieu en 2001 à Bienvenue, pour le festival Nouvelles Scènes de Dijon, dans le sous-sol d’une usine. A cette occasion, il entreprend une collaboration musicale avec Franck Krawczyk qui va perdurer.

A l’aube de l’an 2000, Boltanski réalise des projets à la fois utopiques et universels, dont le premier Les Abonnés du téléphone, acquis par le Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris est mis à jour régulièrement. Boltanski tente de représenter l’humanité entière, en collectant les noms et adresses de toutes les personnes figurant dans les annuaires, en entreprenant un recensement de l’humanité.

2003-2009

C’est le prolongement du travail déjà mené dans les années 1990 sur des listes nominatives qui l’amène à de vastes entreprises évolutives comme Les Archives du cœur. Ce catalogue de tous les battements de cœurs de la terre, destiné à s’enrichir au fil des années, est, depuis 2008, abrité sur la petite île de Teshima au Japon. Sur cette île, sont conservés dans un simple édifice, inspiré des maisons des pêcheurs, plus de 100.000 pulsations vitales recueillies depuis des années dans le monde entier. On peut enregistrer les siennes sur place ou consulter celles d’amis ou de membres de sa famille. L’artiste l’imagine comme un lieu de pèlerinage dédié à la mémoire d’un proche et plus généralement à l’essence de la vie. Une ambition qui prend de l’ampleur avec les pavillons que l’artiste a prévu de construire sur les cinq continents, dans un espoir de participation planétaire et en lien avec la base de donnés-mère de Teshima. Le pavillon asiatique a déjà été bâti dans un village reculé de Chine.

Parallèlement à ces projets universels, Boltanski renoue avec le thème de l’autobiographie dans la hantise de sa disparition. En 2003, lors de l’exposition Entre-temps qui ouvre le jour de son anniversaire à la galerie Yvon Lambert à Paris, l’artiste se concentre sur ce qui reste de lui. Tel un suaire, son visage projeté sur une surface, accueille le public. Quelques années plus tard, paraissent un récit autobiographique, fruit des longues conversations avec Catherine Grenier, publiées dans La Vie possible de Christian Boltanski, (Paris, Seuil 2007), ainsi que le premier tome du catalogue raisonné de ses œuvres auquel il travaille avec Bob Calle. Il se consacre de plus en plus à des œuvres au contenu autobiographique parmi lesquelles Vie possible (2001) où il rassemble ses propres archives dans vingt armoires murales ; 6 septembres (2005) une sélection d’images télévisées passées à cette date, le jour de son anniversaire ; Autoportrait (2008) où il montre son visage vieillissant. Il en est de même pour The Life of C.B. (2010-21), des milliers de vidéos qui enregistrent chaque moment de sa vie dans son atelier et qui sont conservés au musée MONA à Hobart en Tasmanie, propriété de David Walsh. Ce collectionneur, joueur professionnel a parié sur la date de la mort de l’artiste qui, acceptant le défi, lui a proposé un achat en viager ; il a ainsi été filmé nuit et jour dans son atelier et les enregistrements étaient visibles en direct en Tasmanie et stockées. Le sujet du temps qui passe est aussi celui de l’Horloge parlante (2003), installée depuis 2009 dans une crypte de la cathédrale de Salzbourg.

Pendant ces années, Boltanski travaille beaucoup au Japon où participe entre autres à la Triennale d’Echigo-Tsumari : il expose Les Linges à la première édition en 2000 et avec Jean Kalman The Last Class (2009), installation devenue aujourd’hui permanente. En 2006 il reçoit le Praemium Imperiale décerné par la famille impériale du Japon pour son œuvre majeure dans le domaine de la sculpture.

2010-2013

La disparition devient le thème majeur de son travail où les enregistrements autobiographiques accompagnent une création plastique éphémère. Soumis à un très grand désir d’effacement, l’artiste, comme il l’a souvent déclaré, ne fabrique plus rien de permanent. Il réalise en effet de monumentales installations temporaires où tout ce qui est construit sera détruit. L’œuvre autonome est abandonnée au profit d’une élaboration in situ composée d’éléments trouvés avec lesquels il organise des dispositifs qui sont réduits à néant une fois l’expérience cessée.

Deux grandes installations témoignent de cette orientation. En 2010 il envahit le Grand Palais dans le cadre de « Monumenta » avec Personnes ; l’année suivante, le public de la 54e Biennale de Venise est saisi par Chance, énorme structure s’élevant dans le Pavillon français. Dans les deux cas, Boltanski mène une réflexion sur le hasard et sur le destin. Dans Chance, au milieu des échafaudages industriels, défile, dans un bruit fracassant, un ruban composé de milliers de portraits de bébés, tirés des faire-part de naissances parus dans des journaux polonais. De temps en temps, une sonnerie s’actionne, telle la fatalité qui s’abat, et le tapis roulant s’arrête sur le visage d’un bébé. Dans les salles attenantes, deux compteurs annoncent respectivement en temps réel le nombre par jour des naissances et des décès sur Terre.

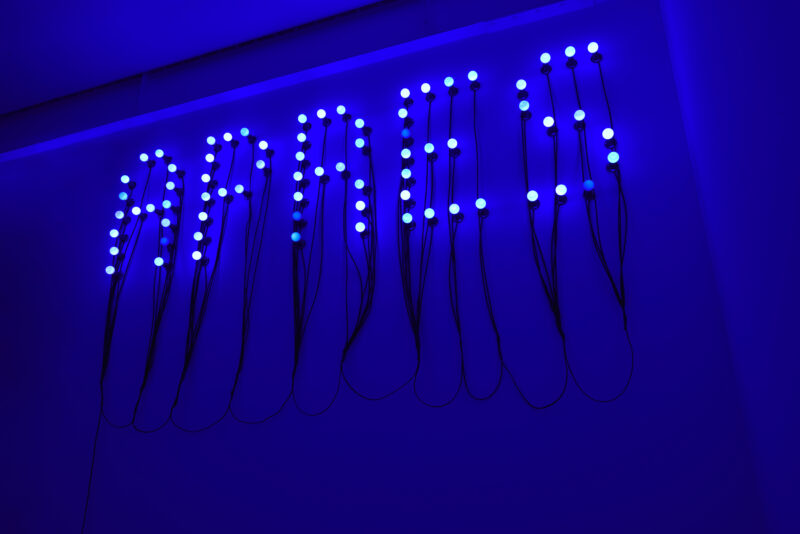

L’installation réalisée pour « Monumenta », occupe l’immense nef du Grand Palais. Avec Personnes, se référant littéralement à une multitude et à aucun, Boltanski qualifie sa recherche à la fois de philosophique, sociale et religieuse. Il choisit de représenter cette coexistence de la vie et de la mort en dressant une imposante grue puisant au hasard dans des milliers de vêtements amoncelés en forme de pyramide. Là encore une image mécanique implacable, associée à un bruit affreusement automatique, nous rappelle la brutalité qui régit le sort et qui dicte la condition humaine. Refaite pour l’Armory Show à New York ainsi qu’au Hangar de la Bicocca à Milan en 2010, l’installation, dans des dimensions toujours plus disproportionnées, se dresse sur 9 mètres piochant dans le tas de vêtements qui remplit le bassin du Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art en 2012. Parallèlement à Personnes au Grand Palais, ouvre « Après » au MacVal, un paysage d’après la mort, peuplé de fantômes, lieu spectral, au climat très proche des pièces de Tadeusz Kantor qui ont joué un rôle déterminant dans l’œuvre de Boltanski. Quelques années plus tard le parterre d’ampoules de Crépuscule (2015) s’éteint jour après jour nous rappelant ce sort inexorable.

Parallèlement sa volonté de toucher un public toujours plus vaste et au bout du monde se traduit en des nouveaux projets. En 2012, il lance Storage Memory, un site où l’abonné reçoit chaque mois, moyennant 10 euros, dix vidéos d’une minute, muets, tournés avec une petite caméra HD durant ses voyages, des « cartes postales de sa vie ».

2014-2021

Jouant la fragilité jusqu’à la disparition, son travail devient de plus en plus impalpable, fait de lumière, de sons, d’effets et tend au périssable, au transitoire, à l’impermanence. Les installations Animitas (Chili), (2014) et Animitas Blanc (2017) et Animitas (Mères mortes) (2017) sont réalisées à partir de deux longues vidéos reproduisant les œuvres in situ, dans le désert d’Atacama au Chili, sur l’île d’Orléans au Québec, près de la Mer Morte en Israël. Réalisées à des endroits symboliques pour rendre hommage aux morts, tels des autels de mémoires, des clochettes japonaises sont accrochées à des piquets plantés dans le sol, dessinant la carte du ciel le jour de la naissance de l’artiste. Filmées en plan fixe, du lever au coucher du soleil, les clochettes tintinnabulent, agitées par le vent. Dans l’installation à chaque fois récréée, la vidéo est mise en situation ; l’expérience du désert aride se prolonge au sol par une étendue de fleurs fraiches et fanées, le désert glacé est suggéré par une jetée de papiers de soie froissés.

Il confie de plus en plus la mémoire à des agents éphémères, en particulier aux sons. A mi-pente du Mt. Danyama sur l’île de Teshima au Japon, Boltanski installe, en 2016, la Fôret des murmures, 400 clochettes portant le nom d’un être aimé tintent sous l’effet de la brise. L’œuvre est permanente et vouée à s’enrichir de nouvelles clochettes.

En 2017 il installe proche de Bahía Bustamante au nord de la Patagonie dans le cadre de Bienalsur, sur un site où se réunissent des baleines, trois immenses structures métalliques qui reproduisent les sons des cétacés lorsqu’elles sont activées par le vent, nous donnant la possibilité d’établir un dialogue avec ces êtres légendaires. Le triptyque vidéo Misterios naît de cette expérience. Quelques années auparavant, durant la 50e Biennale de Venise, des haut-parleurs dissimulés, ont diffusé des aboiements poignants de chiens errants : Entendre les chiens est une pièce sonore à travers laquelle Boltanski nous invite à prêter attention à ces lamentations, à ces communications ancestrales.

Durant la dernière décennie de sa vie, il s’intéresse de plus en plus à la transmission, préférant le récit à l’objet, créant une expérience éphémère et émotionnelle transmise oralement plutôt qu’une relique tangible. Passionné par la tradition orale qu’elle soit religieuse, mythologique et en ne vantant aucune pratique de lecture, il était friand de toute anecdote, conte, blague, croyance populaire. Durant ces dernières années il vise à solliciter un éveil en posant des questions qui demeurent sans réponse.

En réutilisant ses œuvres dans des rétrospectives qui se veulent davantage des parcours ou des chemins de croix, comme il les définit lui-même, il expose avec succès au Israël Museum à Jérusalem, au Power Station (PSA) à Shanghai, au Centre Pompidou qui, lieu de sa première rétrospective en 1984, est aussi le théâtre de sa dernière. Son ultime œuvre, Subliminal, quatre écrans panoramiques disposés en forme de croix et suspendus à un demi-mètre du sol, montre les images d’une nature luxuriante et innocente dont la vie paisible est perturbée par la superposition, pendant quelques centièmes de seconde, de scènes de massacres et génocides perpétrés par l’homme au XXe siècle. Il met en exergue ces procédés psychiques inconscients qui échappent à toute cérébration et glorifie la vie malgré ses horreurs. La pièce est présentée pour la première fois à la galerie Marian Goodman de Paris en début d’année 2021 au sein de son exposition monographique « Après ».

Christian Boltanski décède le 14 juillet 2021 à Paris alors qu’il préparait ses rétrospectives au Musée d’art contemporain de Busan (Corée du Sud) et au Musée du Manège à Saint-Pétersbourg. Cette dernière qui devait s’inaugurer au moment du déclenchement de la Guerre en Ukraine, n’ouvrira pas ses portes.

Depuis le début, son œuvre s’attache à soigner dans la perception de chacun le caractère éphémère de la condition humaine dans son cours indifférent, dans un mouvement à l’infini, inhumainement cyclique.

Annalisa Rimmaudo